I walk into school this morning, I take in the familiar scene in the hallway outside my classroom. A boy lays sprawled across the floor with his head on a backpack, trying to catch a few minutes of rest before the bell. Down the hall, a whispering pack of girls complains about how nervous they are about this week’s test. One brandishes a fat stack of color-coded flashcards and boasts that she studied until 2:00 a.m. Another pair of students exchanges notebooks, furiously scribbling the answers to last night’s homework. I shake my head. Since when did sleep deprivation and stress become a high school rite of passage?

You don’t have to be a doctor to recognize that school-related stress is unhealthy. Any student, parent, or teacher would tell you that students spend too much time worrying about their grades. Many students believe they must get A’s in every class, even while playing a sport, volunteering, working, and rehearsing for the play. If they fall off the treadmill, even for a moment, they might squander their chances of getting into a good college, finding a good job, and living a happy life.

That’s a lot of pressure for an unpaid gig, if you ask me. Where does it come from? I don’t think teenagers put this upon themselves. No, it’s more likely that students are responding to the environment we, the adults, have created for them.

Sir Ken Robinson, whose TED talk “ Do Schools Kill Creativity?” has over 41 million views, argues that the culture of high academic achievement has created an entire generation of children who are “frightened of being wrong….And we’re now running national education systems where mistakes are the worst thing you can make.” If students are afraid to be wrong, they will never take a risk, never ask a question, never learn from a mistake. What a terrible irony. The institution designed to prepare students for the real world deprives them of the skills most essential to their success: learning how to fail and learning how to learn.

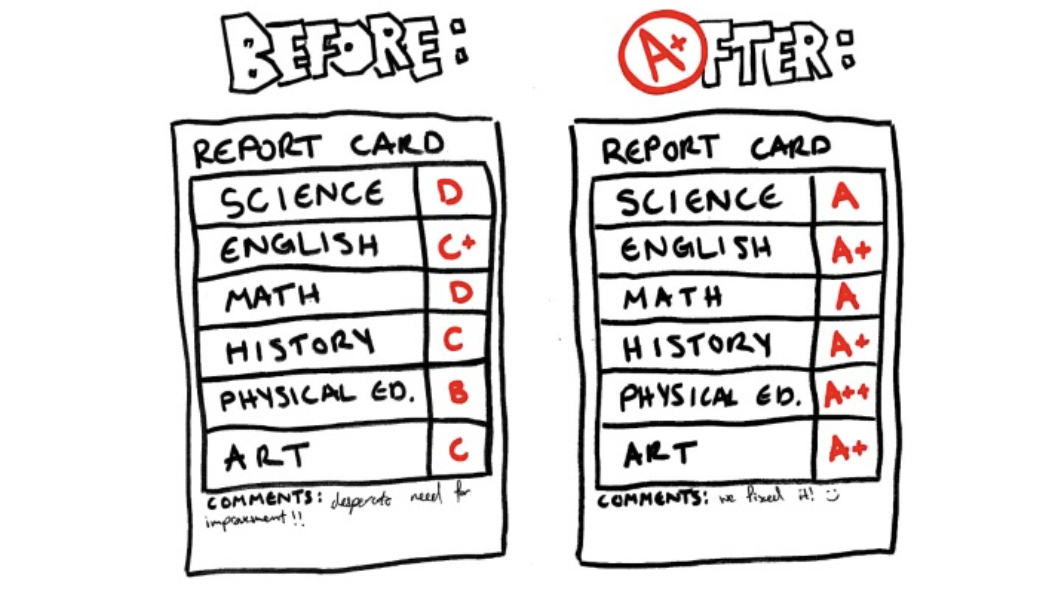

Schools can and must do better. Despite my frustration with the way things are, I am an optimist. I believe the first step in fixing our school system is to change the way we assess students. Our grading system is broken. If I had it my way, I would eliminate grades entirely. They do nothing to help students learn and should be abolished. I realize, however, that the world isn’t quite ready for that radical of a change. That is why I am working with three other Yorktown teachers–Mr. Bunting and Mr. Barkan in English and Mr. Carroll in Physics–to implement something called standards-based grading. This new system offers common-sense fixes for broken grades that help students shed their fear of failure and take charge of their learning.

Fix #1: Give Students Detailed Feedback

The purpose of grades is to report on students’ knowledge and skills based on their work in the class. However, in the traditional grading system, this meaning is easily lost. The first problem with traditional grading is that it tries to represent achievement with a single number. What exactly does an 82% in English actually mean? How much of that 82% was based on your understanding of Lord of the Flies? How much was based on vocabulary? What about grammar and writing? If you don’t know your specific strengths and weaknesses, how are you supposed to improve? It’s really difficult to know without an extensive excavation of all your old assignments or a long conversation with your teacher.

Standards-based grading remedies this problem by providing students with a score for each of the concepts and skills (also called standards) taught in the class. Instead of using the 100-point scale, I now use a 1-4 scale, which very simply corresponds to beginning, developing, proficient, and advanced levels of skill mastery. The nebulous 82% in English under the old system has been replaced by a developing score in reading comprehension, a proficient score in use of text evidence, a proficient score in use of punctuation, and a proficient score in thesis statements. With this feedback, students (and teachers!) can more easily identify strengths and weaknesses and set goals for improvement.

Fix #2: Assess Knowledge & Skills, Not Behavior

Another problem with traditional grades is that part of that 82% in English may have nothing to do with your understanding of English concepts at all. It is common practice for teachers to deduct points for late work, issue zeroes for missing work, and offer extra credit. Does a zero for a missing assignment really mean you understood zero percent of the content? Oftentimes, a grade simply tells us how much work a student did and whether or not it was completed on time. Some will argue that students should be graded on how responsible they are because that is a valuable “real world” skill. It may very well be. However, responsibility is a behavior, and it has nothing to do with the English curriculum. Teachers and parents should find a way to teach responsibility without threatening students with a bad grade.

Standards-based grading looks only at the work students have done. How can I give a student a score on work they haven’t turned in? There are no late penalties and no extra credit. Missing assignments are treated as missed opportunities. This simply means that in order to practice and demonstrate mastery of the skills assessed by the missing assignment, a student either needs to make up the assignment or come up with another way to demonstrate their learning. There are many opportunities for the student to demonstrate mastery of each skill over the course of the year. This change takes the pressure off of students who have missed class or who struggle with other issues outside of school. The grade is about what you know and can do, not about how much work you’ve done.

Fix #3: Only The Finish Line Matters

The final problem with traditional grading is that it fails to recognize that learning is a process that happens at a different rate for each student. In the real world, only the finish line matters. It doesn’t matter that you started your marathon training running really slowly if, by the time race day arrives, you run fast enough to win. Grades don’t work that way. Instead of looking at where students are by the end of the year, we take an average of all of their practice. For many students, grades feel like a record of their shortcomings, an artifact of their fall from grace, a catalog of sins awaiting judgment on graduation day. This focus on the negatives instead of the positives is what makes students afraid to fail and stops them from learning.

Standards-based grading kicks the law of averages to the curb and looks instead at what the student knows and can do by the end of the year. The final course grade is based on how many standards a student has mastered. I ask my students to think about how they would like to be graded for playing a song on the ukulele. Let’s say a student plays the song twenty times and absolutely bombs the first eighteen attempts. She keeps practicing, however, and, all of a sudden, something clicks. She can play the song perfectly after that. Has she mastered this song? Of course. Shouldn’t her grade reflect that? Of course. This applies to any skill. You don’t succeed until you do, and you shouldn’t be penalized for practicing. Our grading system should reflect that.

So Far, So Good

This is a new system, and, like anything new, it comes with growing pains. In order to make standards-based grading work, we have to let go of the old way of thinking and embrace the future. That’s hard to do, especially at the high school level because “getting good grades” is so deeply ingrained into our definition of academic success. I know there will be challenges along the way, but I believe wholeheartedly that this is the right thing to do for students.

I can’t say this is the panacea to all of education’s ills, but it is a good start, and it’s something I can actually change as a teacher. I can say that since switching to standards-based grading, I have noticed that my teaching is more focused and that my students are more aware not only of what’s expected but of how well they are meeting those expectations. Whenever a student comes to me with a question about his “grade” in my class, we have a conversation about learning. We don’t quibble about late penalties or why points were deducted. It’s really just about where the student is and how he can improve on the next assignment. At the end of the day, all I want to do is help kids learn.

Samantha Kaut • Oct 18, 2016 at 2:02 pm

I really like the idea of the new system because as said, it really focuses on how the student can really improve instead of worrying about their grades. One of the ideas I really liked was getting feedback. This will help a lot of students know what they need to get better at and get students to where they need to be. I also never even thought that the finish line is what really matters. I never would think that what you have accomplished and you are able to do is all that matters at the end of the day. From my experiences, I would always worry and stress about my grades a lot throughout the school year. This new system has got me into a completely different way of thinking and a different mindset.