From 1976 to 1986, the state of California was terrorized by a brutal series of 120 burglaries, 45 sexual assaults and 12 murders. The suspect, later dubbed the Golden State Killer, was something of an enigma. His attacks were always strikingly similar; the victims were typically white, upper middle class and living in quiet, protected suburbs throughout the state of California. He had a habit of studying his victims before his attacks took place, often broke into their empty homes in order to familiarize himself with names and the layout of houses, to develop his plan of attack. Underneath couch and chair cushions he would leave ropes and nylon cords which he would later use as weapons. When he carried out the attack, he would break into the home once again, often wearing a ski mask, and shine a flashlight into his victim’s eyes before carrying out whatever horrific plan he had previously laid out. As his ten-year reign of terror went on, he became more confident and more sadistic, helping himself to whatever food was inside of his victims’ refrigerators, forcing individuals to assist him in carrying out the murder of their significant other. Each time, his attacks were brutal, depraved and seemingly unsolvable.

In 1986, after his final attack, the case of the Golden State Killer went cold. His murders, burglaries and sexual assaults were carried out with a good deal of forethought, each one making his identity seem more and more difficult to decipher. It certainly did not help that the last time anybody had lived to be able to describe the killer had been roughly seven years earlier, in 1979. In that time period, the Killer’s appearance and tactics could have changed dramatically, the only consistent factors used to link attacks to him being the footprint of his size nine tennis shoes and his propensity towards using nylon cords. Thus began a 30-year period of increasingly quiet obscurity for the Golden State Killer, who slowly faded from the public eye, set to join the ranks of other infamous, unnamed criminals like the Zodiac Killer. California was eager to forget the mayhem and terror wreaked by the Golden State Killer; indeed, it seemed as though he would be able to elude capture once and for all.

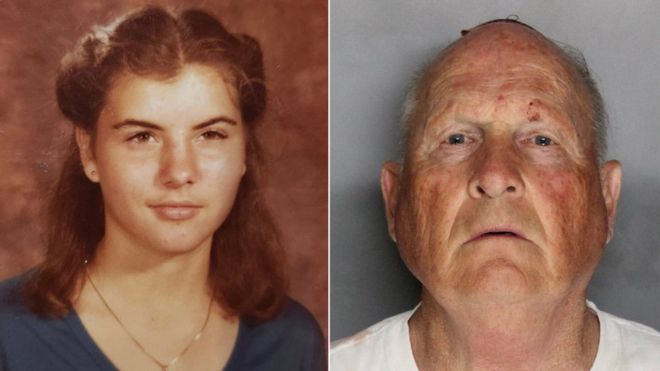

Then, in June of 2016, something changed. The case was suddenly given new attention, with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and California law enforcement agencies announcing a $50,000 reward for his capture. At some point between then and April 25, 2018, however, after a 40-year search, authorities have announced the arrest of their primary suspect, a 72-year-old former police officer by the name of Joseph James DeAngelo. DeAngelo, in addition to having worked in the police departments of Auburn and Exeter, California, served in the United States Navy during the Vietnam War. He was eventually discharged from the police force after being caught shoplifting a can of dog repellent and a hammer from a drugstore.

From such a description, one would not expect DeAngelo, a former cop and petty shoplifter, to have been the infamous Golden State Killer. After all, several of the crimes were committed while DeAngelo was serving as a police officer. DeAngelo seemed so inconspicuous, in fact, that it took more than 40 years to find him.

The methods that were used to find DeAngelo have given rise to a fair amount of controversy. DeAngelo was singled out through the use of public DNA tracing services; the investigating officers submitted DNA evidence found at crime scenes to public DNA databases, which they then used to search for individuals who may be related to the perpetrator, eventually ending up with a short list of families. Those families were then cross-referenced with the circumstances (e.g. time and location) under which the murders were committed.

Where the controversy arises, though, is in the potential of such a process when applied to other circumstances. The investigating officers uploaded DNA that was not their own to a public database, which has led some to point out what they see as being serious privacy risks for normal, law-abiding citizens who have their DNA submitted to similar services without their knowledge or consent. If someone were to send a friend or family member’s DNA to a service such as Ancestry, 23andMe, or GEDMatch, their personal genetic code is no longer private information; their DNA can be bought and sold, just like any other information that social media companies already sell. To make matters worse, when DNA is submitted, there is often no way to have it removed or deleted. While the collection and submission in the case of the Golden State Killer resulting in a likely suspect seems justified, many have begun to question the effects of applying such a procedure to suspects who turn out to be innocent. If they are not acquitted, their identity has been compromised without proper cause.

Despite questions of ethics or morality, the public can at least rest assured knowing that a man who wreaked infinite terror and havoc upon a vast number of people has likely been captured, and thus will never cause death and destruction again. Even still, the debate surrounding the ethics of DNA evidence used during investigations will likely remain a hot-button issue in the months, or possibly years to come, the results of which have the potential to change the future of how crimes are investigated in the United States.