For the early-rising residents of Hawaii, the morning of January 13 was just another day in paradise. The sun had risen at 7:11 a.m., and locals and tourists alike were gearing up for another normal day.

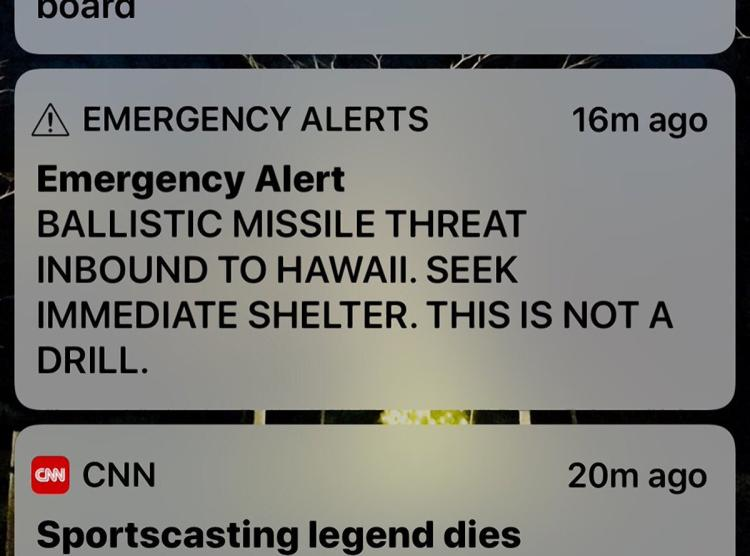

That all changed shortly after 8 a.m., when a mass alert appeared on the screen of every smartphone in Hawaii. The alert read in all caps: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” For the next 38 minutes, Hawaii was sent into a state of panic, with many left wondering if the next few minutes would be their last.

“[My family] was pretty freaked out… there were police everywhere…. people were fleeing the beach,” said sophomore Mackenzie Nemoto, who was visiting Waikiki Beach in Honolulu when the alert was sent out.

Morgan Pugh, a former Yorktown student who now attends the University of Hawaii at Manoa, was able to paint a similar scene of panic.

“Nobody thought it was a drill at first… people were panicking and running around, calling their family members to say goodbye,” Pugh said.

To many people, both in Hawaii and abroad, an event such as this is horrifying. For 38 minutes, people were left thinking that they, and everything which they held dear, would perish. What is even more terrifying, however, is that this is not the first time that such a false alarm has been issued.

In 1971, during the Cold War, the American public was falsely warned via radio and television that thermonuclear war was about to break out. More recently, in September of 2017, all United States military personnel stationed in South Korea, as well as their families, received a false alert via smartphone instructing them to evacuate the Korean peninsula as soon as possible. The false alarm issued to American soldiers carries as much, if not more, significance as the recent one issued in Hawaii, as a statement such as this could be a clear indicator of military action against North Korea. In the latter scenario, it is still unclear what caused the alert to be sent, although hacking is a realistic possibility.

So, what caused the Hawaiian alert to be sent in error? Thankfully, it looks like we have a substantial answer from the state of Hawaii. Apparently, during a routine test of the emergency missile warning system, an employee, whose identity has not been disclosed, managed to select “Missile Alert” rather than “Test Missile Alert” from a dropdown menu. On January 30, however, it was found that this was not exactly the whole story. As it turns out, the employee who clicked on the wrong item was not entirely to blame. A night-shift supervisor for Hawaii’s emergency alert system deemed it necessary to test the day-shift employees by having them go through the steps of sending out an emergency alert. The day-shift supervisor was informed that this test was going to happen, but did not understand that it was intended for his own employees. As a result, neither supervisor (nor their employees) were prepared to deal with the drill itself. The night-shift supervisor then called the day-shift team and (as is apparently standard to protocol) pretended to be an employee of the Pacific Command, the agency responsible for detecting and reporting incoming threats. The night-shift supervisor then continued to play a recorded message for the day-shift team which (contrary to protocol) included the phrase “This is not a drill.”

The government’s explanation for the false alarm has raised numerous eyebrows. If an employee managed to send 1.4 million people into panic just by selecting the wrong item from a drop down menu, then how hard would it be for some other potentially cataclysmic event to occur due to simple human error? How could one government employee be given the power to tell the entire population of Hawaii that they were about to experience a nuclear apocalypse, and not have been told which button to press in order to avoid doing so? What is even worse is that there was no system in place for declaring a false alarm, which resulted in an almost 40-minute period between the alert being issued and it being officially declared a false alarm. Furthermore, how was it possible for the message that was given to the day-shift employees to not only fail to include the fact that the missile alert was a drill, but to go so far as to break protocol and attempt to trick the employees by telling them that the alert was legitimate? The lack of communication, as well as mitigation of risks, concerning such important matters is shocking. Such careless holes in the United States defense system could pose a serious threat to national security, and these security threats deserve to be addressed.

Thankfully, Hawaii has taken steps to avoid an incident like this from happening in the future. The government has introduced a “cancellation button,” which can be pressed to immediately correct any mistake pertaining to emergency alerts. Additionally, a two-person verification system has been introduced, which requires the confirmation of two seperate people in order for any alert of that magnitude, false alarm or the real deal, to be sent out.

It is alarming to see the devastation which can occur as the result of a simple mistake, and in this day and age, the United States can no longer afford to have such dangerous holes in its national security. What happened in Hawaii should serve as a wake-up call that encourages the United States to take a serious look at its emergency infrastructure, lest we continue to make these same mistakes.