February is an important month, and not because of love or football. Since 1976, the month of February has been designated as Black History Month. It is the time to celebrate and remember the achievements of African Americans who play a central role in U.S. history. Canada and the United Kingdom also celebrate this month to highlight the achievements of black people in their own history.

The start of Black History Month grew from a national Negro History week that was founded in 1926 by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). This week was chosen to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass, a prominent abolitionist and social reformer, and Abraham Lincoln, and inspired schools and communities across the nation to organize different history clubs and lectures. As part of the Civil Rights movement, the week grew into a month, and President Gerald R. Ford officially recognized Black History Month in 1976. It was an important event in history that helped push African American identity beyond slavery and segregation.

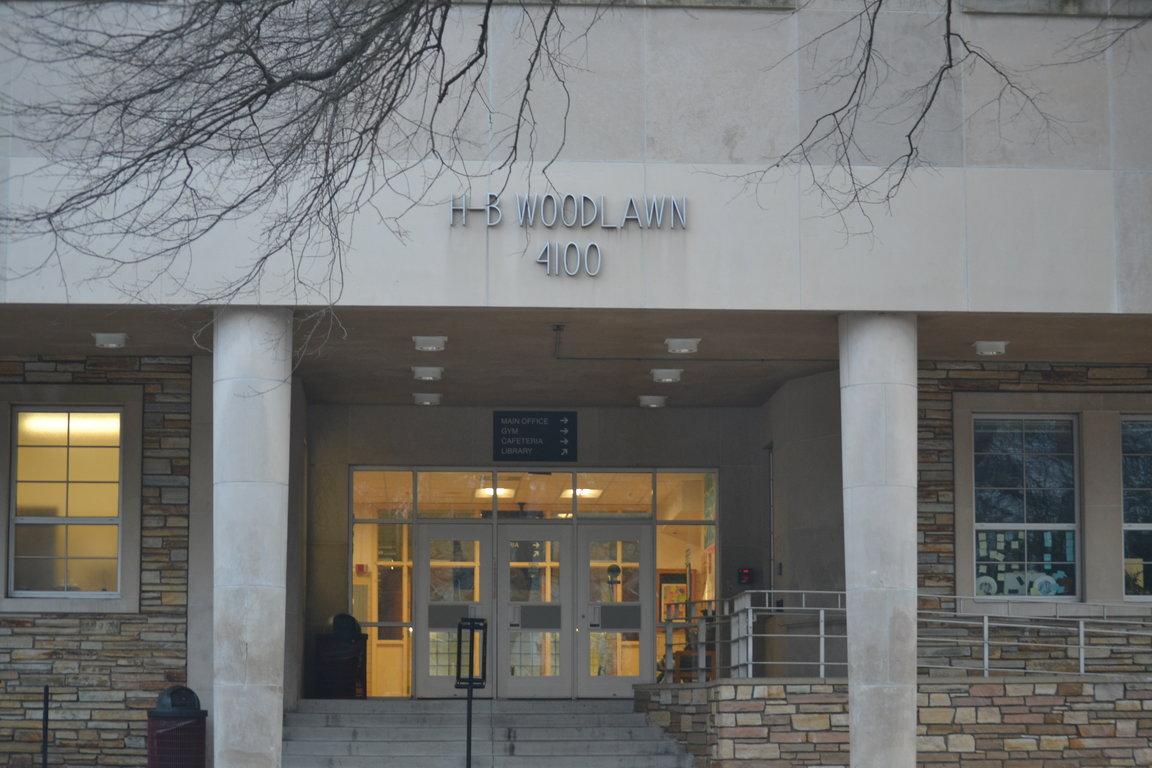

However long ago racist events such as slavery and segregation may seem, they were both real and prevalent in Arlington County. Only a couple of weeks ago was the 57th anniversary of the desegregation of public schools in Arlington County. Before there was an H-B Woodlawn, the school was Stratford Junior High and it was the first to open its doors to African American students in Virginia.

Sociology teacher William Wheeler, who lived in Arlington when Stratford desegregated, explained the county’s situation during this time.

“Arlington was caught between the court orders to desegregate the schools under the Brown decision and the Byrd Machine’s [the political machine of the governor of Virginia] leadership of the ‘massive resistance’ movement to school desegregation,” said Wheeler.

By agreeing to integrate, Arlington angered the state and the Arlington school board was taken over. That did not stop the process of desegregation, and the Arlington Board decided to integrate Stratford. But why was Arlington agreeing to integrate despite the pressure from the rest of the state?

“Arlington was culturally far different than the rest of Virginia. Many residents had come from other areas of the country after World War II to work for the government. They came from areas where legal segregation was not entrenched, although de facto segregation was countrywide, and still is. There were old line southerners here who made noise about the integration, but as a whole, the process went without much bother,” said Wheeler.

Despite the grumbling and the Byrd Machine’s attempts to prevent desegregation in Virginia, the integration process continued and the high schools in Arlington desegregated next. Eventually by the mid-1970s, the entire state had desegregated. It was a long, drawn out process that met massive resistance, but eventually the schools were no longer perpetuating the racism that divided society. This time was revolutionary, and is especially relevant for Black History Month.